In Search of a Boy Named Chester

A gift to my father for his 100th birthday

BY FORD S. WORTHY

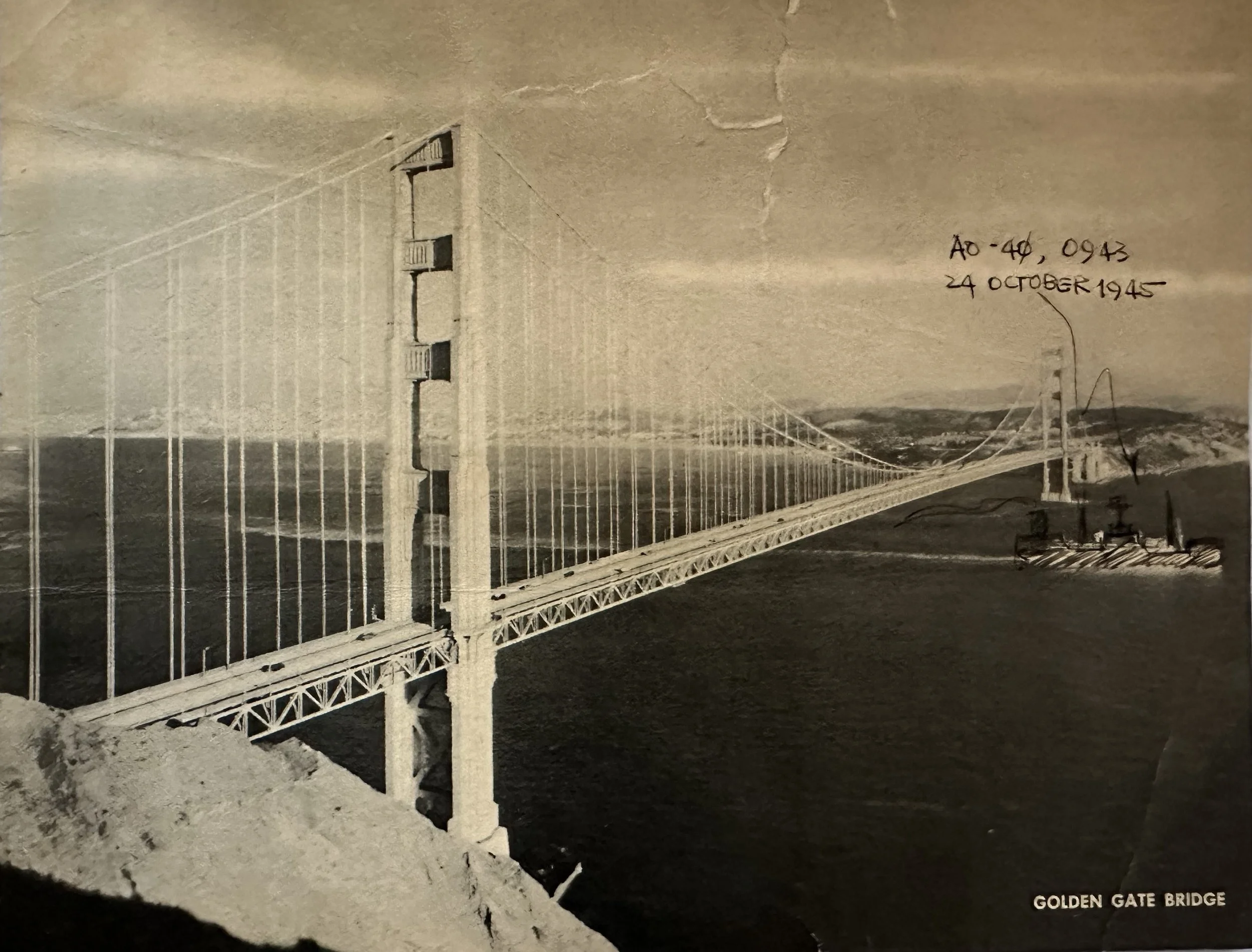

Shortly after the end of World War II, a 21-year-old Navy officer – just back after a year at war in the Pacific – was eager to return to his small hometown in eastern North Carolina.

At the San Francisco airport, a mother traveling to Omaha offered him her seat – a patriotic gesture of gratitude, he believed. There was one condition: the sailor would need to accompany her 10-year-old son and see him safely to his grandmother in Omaha.

The boy’s name was Chester. The sailor never forgot him.

Nearly 80 years later, the sailor’s son sets out to give his father a special 100th birthday gift: to discover what became of that precocious boy. Part historical detective tale, part exploration of the ties that bind a father and son, In Search of a Boy Named Chester is a story about memory, family, and how even the most fleeting encounters can reveal who we were and who we may become.

“A moving ode to fathers, sons, and the extended families we create.”

Kirkus Reviews

New book chronicles NC veteran's unexpected encounter on long journey home from WWII

Featured on WUNC North Carolina Public Radio - FM 91.5